On April 21, 2024, Africa’s oldest park celebrated 99 years of existence. This pre-golden-age anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on the legacy of conservation to be left to posterity, and to pay tribute to all the lives lost to preserve this endangered global heritage, says Méthode Uhoze, Director of External Relations at Virunga National Park.

Created to preserve mountain gorillas, Albert Park, now Virunga National Park, has expanded over the years to cover an area of 790,000 ha, with a biodiversity unique in the world.

Its rich fauna and flora, as well as its subsoil, attract the covetousness of many, including foreign countries. This makes the task of conservation a daunting one. 99 years of existence are also rivers of tears of resilience and an opportunity to pay tribute to all those who sacrifice themselves for Virunga. Above all, we need to think about the future,” emphasizes Méthode Uhoze, Director of External Relations at Virunga National Park:

“The first experience of 100 years of conservation in Africa. It’s a golden opportunity to share our experience with other African countries, but also to think about how to put things right where things haven’t gone so well. Certainly, the whole world will want to come and learn from our experience how we’ve been able to achieve 100 years of conservation.

This should be a wake-up call to everyone, the authorities and the population, as to the experience to be given to all these countries. The current context is not favorable in view of all that is currently happening in this part of the DRC. We inherited this park from our forefathers, and we all have a duty to pass it on to future generations. We call on everyone, within the limits of their power, to support the conservation efforts undertaken in the Virunga National Park, through all the programs implemented for the benefit of the local populations.

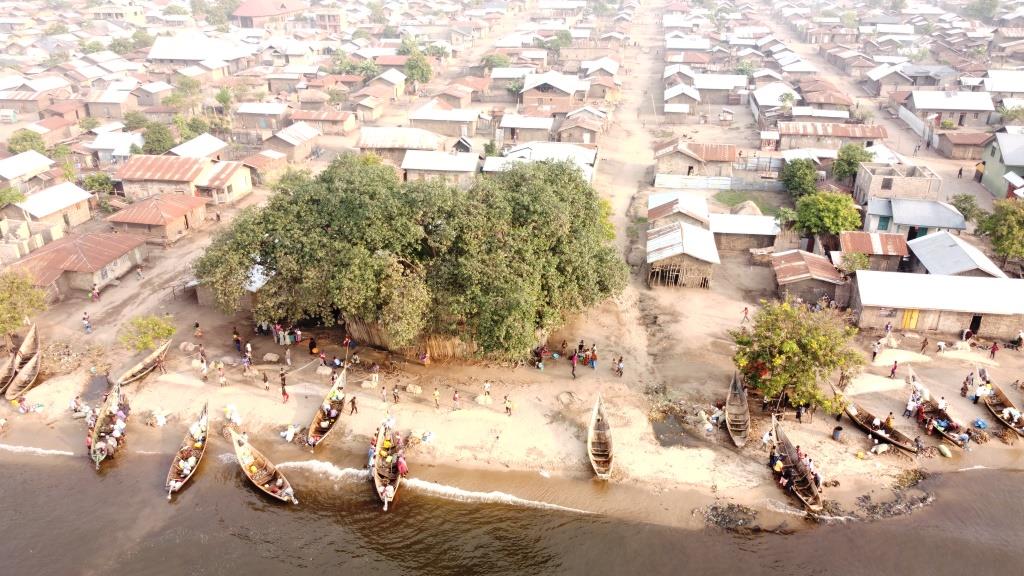

In fact, these 99 years have been punctuated by conflicts, so much so that the local populations have doubts about this preservation. Some projects have been carried out, but have not yet reached the target farmers. Many farmers do not have the financial means to pay for an electricity subscription, even if only for domestic lighting. Charcoal and firewood remain the main source of energy for households in the region, with a good deal coming from Virunga National Park.

As conurbations grow, so do old boundary disputes, since the park was created without any concessions to the inhabitants of these areas.

Conflicts have arisen between traditional chiefs and park managers in several regions. There is also poaching and illegal mining inside and outside the park, which serves as a larder and hideout for negative forces.

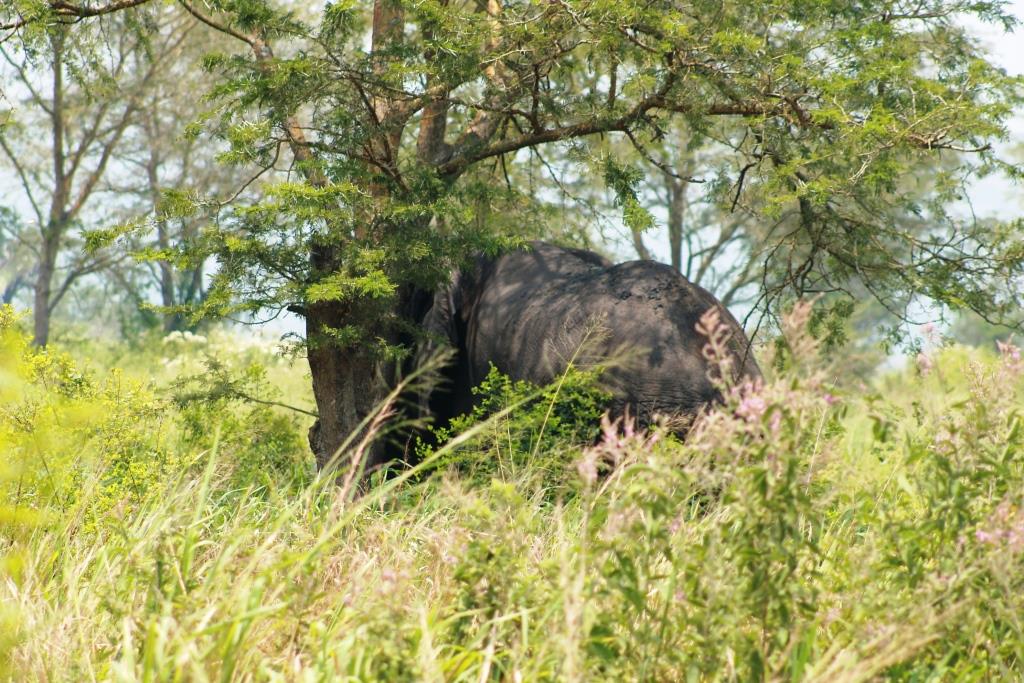

The Virunga National Park boasts an incomparable diversity of habitats, from swamps and steppes to the eternal snows of the Rwenzori, at an altitude of over 5,000 m, via lava plains and savannahs on the slopes of volcanoes.

Some 20,000 hippos frequent its rivers, the mountain gorilla finds refuge here, and birds from Siberia visit.

Virunga National Park is distinguished by its chain of active volcanoes and a rich diversity of habitats that surpasses that of any other African park, from steppes, savannahs and lava plains, swamps, lowlands and Afromontane forest belts to its unique Afro-alpine vegetation and the icefields of the Rwenzori mountains, whose peaks rise to over 5,000 m. The site includes the spectacular Rwenzori and Virunga massifs, home to two of Africa’s most active volcanoes. The site includes the spectacular Rwenzori and Virunga massifs, home to Africa’s two most active volcanoes.

The great diversity of habitats has given rise to exceptional biodiversity, including endemic species and rare, globally threatened species such as the mountain gorilla.

Virunga National Park offers some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in Africa. The rugged Rwenzori Mountains, with their snow-capped peaks, cliffs and steep valleys, and the volcanoes of the Virunga Massif, with their Afro-alpine vegetation of tree ferns and lobelia, and their densely forested slopes, are places of exceptional natural beauty. Volcanoes, which erupt every few years, are the dominant landforms of this exceptional landscape.

The Park boasts many other spectacular vistas, including the eroded valleys of the Sinda and Ishango regions.

The Park is also home to large concentrations of wildlife, including elephants, buffalo and Thomas’s cobs, and the highest concentration of hippos in Africa, with 20,000 individuals living on the shores of Lake Edouard and along the Rwindi, Rutshuru and Semliki rivers.

Virunga National Park lies at the center of the Albertine Rift, itself part of the Great Rift Valley.

In the southern part of the Park, tectonic activity due to the extension of the earth’s crust in this region has led to the emergence of the Virunga massif, made up of eight volcanoes, seven of which are located wholly or partly within the Park. These include Africa’s two most active volcanoes – Nyamuragira and nearby Nyiragongo – which together account for two-fifths of all historical volcanic eruptions on the African continent, and are characterized by the extreme fluidity of their alkaline lavas.

Nyiragongo’s activity is of worldwide importance as a testimony to the volcanism of a lava lake: the bottom of its crater is in fact occupied by a quasi-permanent lava lake, which periodically empties with catastrophic consequences for local communities.

The northern sector of the Park includes around 20% of the Rwenzori Mountains massif, Africa’s largest glacial region and the continent’s only truly alpine mountain range. It adjoins Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains National Park, a World Heritage site, with which it shares Pic Marguerite, Africa’s third highest peak (5,109 m).

Because of its variations in altitude (from 680 m to 5,109 m), rainfall and soil type, Virunga National Park boasts a huge diversity of plants and habitats, making it one of Africa’s most biologically diverse national parks. Over 2,000 higher plants have been identified, 10% of which are endemic to the Albertine Rift.

Afromontane forests account for around 15% of the vegetation.

The Albertine Rift is also home to more endemic vertebrate species than any other region on the African continent, and the Park boasts numerous examples.

The Park is also home to 218 species of mammals, 706 species of birds, 109 species of reptiles and 78 species of amphibians.

It is also home to 22 species of primate, including three great ape species – the mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei), the eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the eastern chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthi), and a third of the world’s mountain gorilla population.

The Park’s savannah zones are home to a diverse population of ungulates, and the biomass density of wild mammals is one of the highest on the planet (27.6 tons/km²).

Ungulates include rare animals such as the okapi (Okapi johnstoni), endemic to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and the red duiker (Cephalophus rubidus), endemic to the Rwenzori Mountains. The Park also features important wetlands essential for the wintering of Palaearctic avifauna.

The park is characterized by a mosaic of extraordinary habitats covering 790,000 ha.

The property is clearly delimited by the 1954 ordinance. Its riches are well protected despite the economic and demographic challenges on its periphery.

The park contains two highly important ecological corridors linking the different sectors: the Muaro corridor links the Mikeno sector to the Nyamulagira sector, while the west coast connects the northern sector to the central sector of the Virunga massif.

The presence of Queen Elizabeth National Park, a contiguous protected area in Uganda, also constitutes a terrestrial ecological corridor linking the central and northern sectors. Finally, Lake Edward is an important aquatic corridor.

The property has enjoyed National Park status since 1925. Its management authority is the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN), an organization that has lost many of its staff in the line of duty.

To ensure the long-term future of the property, the park needs to be managed on a scientific basis, with a management plan that would, among other things, facilitate better delineation of the various zones. Reinforced surveillance would ensure the integrity of the park’s boundaries. It would also reduce poaching, deforestation and pressure on fish stocks (which are likely to increase), particularly from isolated armed groups.

To this end, it is essential to increase the number of staff and equipment available, as well as the training of park personnel.

Improving and strengthening administrative and surveillance infrastructures would help reduce pressure on rare and endangered species such as mountain gorillas, elephants, hippos and chimpanzees.

In view of significant human population growth, the establishment of buffer zones in all areas is both essential and urgent.

Another priority is the establishment of a Trust Fund to guarantee sufficient resources for long-term property protection and management.

The promotion of localized and controlled tourism could increase revenues and contribute to regular funding for the country.

UNESCO provides crucial support for biodiversity in emergency situations.